Shortage of hospital beds in Seoul

Shortage of hospital beds in Seoul

Posted March. 29, 2023 08:24,

Updated March. 29, 2023 08:24

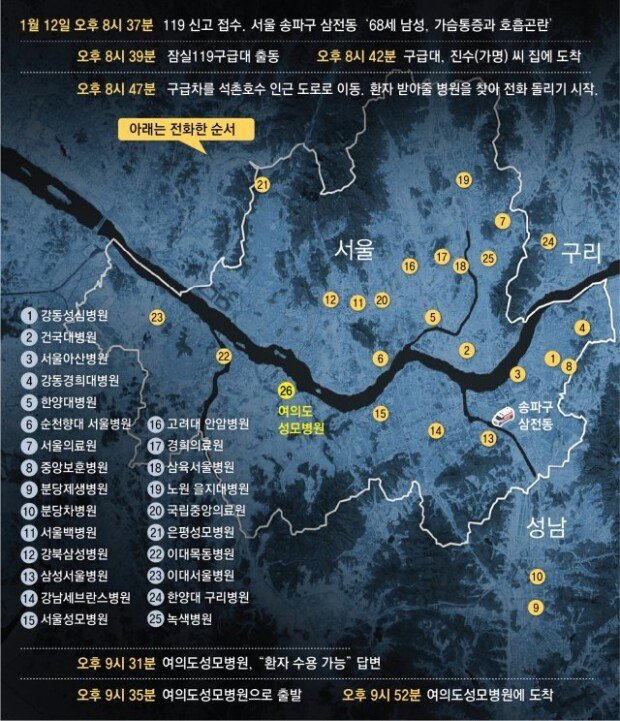

Three men fighting for life in an ambulance with red signs flashing. It was a cold windy day on January 12 as an ambulance stood on a six-lane road near Seokchon Lake in Songpa-gu, Seoul. It was 9:19 PM, so the commute congestion was far gone. Still, the ambulance led by Chief Choi Kyeong-hwan of the Jamsil 119 emergency medical services stood alone as other cars whizzed by.

Jin-soo (alias, age 68), wearing electrodes all over his chest, gasped for breath. He had chest pains and moved to the ambulance at 8:37 p.m.. Already 42 minutes had passed.

Choi continued to make calls. “Eunpyeong Saint Mary doesn’t pick up the phone,” he said. He scrolled down his phone call list with his thumb. He had called Asan Hospital, Samsung Seoul Hospital, Seoul Saint Mary and lastly Eunpyeong Saint Mary. He had made 21 calls after he took the patient.

He picked up the phone again. It would be his 20-second call. A calm voice answered his call, despite the urgency of the situation.

“Hello, you have reached the Regional Emergency Center of Ewha Womans University Mokdong Hospital. Press one to inquire about medical history documents…press zero for other inquires,” the voice said.

Choi pressed zero. He was connected to the emergency room in 59 seconds after speaking to an agent and waited some more. “Sixty eight-year-old patient with chest pains and breathing difficulties. Can you take him?”

Jin-soo had felt chest pains since 7:10 p.m. In the worst-case scenario, it could be myocardial infarction. If this were the case, he needed to get treated within 90 minutes since the chest pains started. He started to feel anxious as he checked his watch. He might have missed the golden time. Choi began to speak faster as he described the patient’s condition.

The ambulance stood alone in the middle of the road in this urgent situation because there was no emergency room to accept Jin-soo.

This situation occurred in Seoul, where 56 large hospitals are located. The last notes of the reporter, who followed Choi’s steps, read, “It took one hour and 15 minutes to arrive at the emergency room of Yeouido Saint Mary’s Hospital.”

“Can’t you find a place near you?” the emergency room person asked, hinting that there were plenty of hospitals in Gangnam. The Ewha Woman’s Hospital in Mokdong was more than 30 minutes away.

“No, they all said they couldn’t accept him.”

“Hold on, please.”

As the silence grew longer, Choi turned to Jeong Jin-woo, who was making calls to other hospitals. “Have you tried?” he asked. “They say no. They don’t have any beds in the ICU,” he replied.

A few minutes later, the emergency room employee returned. “I’m afraid we cannot accept the patient as we do not have any beds,” he said. The conversation lasted three minutes and one second. Choi made his 23rd call. “I can’t believe this is happening when my heart hurts terribly,” said the patient, who had kept his eyes closed to endure the pain, managed to say.

● Patients turned away because there are “no beds”

“My heart is pounding,” said Jin-soo when Choi arrived at his house located in Samjeong-dong in Songpa, Seoul. He grabbed his chest in pain. He started to feel the pain on his way home from work.

The pain grew unbearable at 8:37 p.m. on Jan 12. His wife called 119 and the ambulance arrived in five minutes.

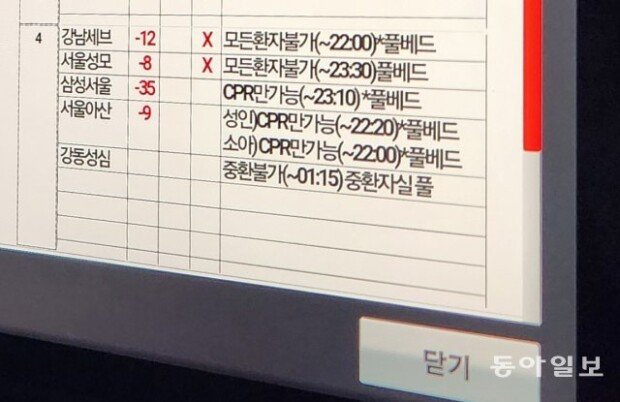

Jin-soo got in the ambulance, but it could not be driven right away. Choi opened his ‘hospital bed dashboard’ app for first aid emergency workers at 8:48 PM and skimmed through the list of hospitals. He saw the number 35 next to Samsung Seoul Hospital. 35 persons waiting – that was hopeless.

Gangdong Sacred Heart Hospital, which was 20 minutes away, was marked as available for beds. The ambulance still could not leave, as there was an alert that said, “No beds in the ICU.” If Jin-soo had to be taken to an ICU equipped with a heart monitor and respirator, they would be back on the road looking for a new hospital.

Konkuk University Medical Center showed availability. Choi called immediately.

“I’m a paramedic in Jamsil, Songpa.”

“Are you currently treated here?” asked the emergency room employee, even before he could finish describing the patient’s condition.

“No, but he has chest pains and…”

“No hospital beds at all, patients are waiting.”

● Maps torn with a lighthouse without lights

There are five large hospitals within a 5-kilometer radius of the patient's home. However, all of them refused to see Jin-soo. They said there were no empty beds in the emergency room or said that there was no doctor to do a cardiac exam. Over Choi's phone, he kept hearing replies beginning with "I'm sorry."

“There are no empty beds in the intensive care unit.” (Hanyang University Hospital)

“We can’t run heart tests at the in the ER.” (Eulji University Hospital)

“There are too many patients with chest pain for any procedure to be done at the moment.” (Korea University Anam Hospital)

Jin-soo's wife was growing anxious. “I thought that if my husband got on the ambulance, getting to the hospital was a breeze,” she said.

A patient with dyspnea whom he was in charge of transfer two weeks ago failed to be admitted to an emergency room. There was no hospital, so an ambulance rushed the patient to a hospital with a marked empty bed, but the hospital said that another unconscious emergency patient was on the way. In the emergency room, patients are treated in the order of life-threatening conditions, not in the order of arrival. Jin-soo could be put at further risk if he was taken blindly to a hospital where other seriously ill patients might be waiting in line.

That night the ambulance seemed to be sailing the open sea with a map only half intact. If an emergency crisis breaks out every night in the middle of Seoul, where medical infrastructure is concentrated, it is reasonable to think that there may be a mechanism with which one will find a hospital where all emergency rooms, intensive care units, and medical staff are fully operational, but it is not the case. So far, attempts to provide 119 with the status of empty beds and doctors on duty in hospitals have been rendered futile.

● ‘If you have a fever, you are still difficult to be treated’

As the call become prolonged, the patient lying down moaned. Choi asked in a loud voice. “Is the pain worse now?” The patient barely nods. "Yes, a little bit… .”

The two are getting antsy. “Is there any update to the National Medical Center?” “Full intensive care unit is full (no availability).” “What about Chung-Ang University Hospital?” “‘Cannot accept any patient.’”

Jin-soo has a low-grade fever of 38 degrees and has been coughing a little for three days. The emergency room staff said no to the patient as they couldn't admit him, because they suspected he had COVID-19 and needed to be tested, but there were no empty beds in the quarantine room.

After failing to find a hospital in Seoul, Choi called Bundang Jesaeng Hospital in Seongnam, Gyeonggi Province. They said they could do a heart test for the patient on condition that he be sent home if he tests positive for COVID-19. It was because he could not be hospitalized because the quarantine room was not available.

“So what if he tests positive for COVID-19?” Jin-soo's wife, full of tears, asked.

Choi explained calmly, fearing that the patient would be surprised, but he felt uneasy. If the patient is COVID-19 positive and has a heart problem, Choi had to continue to pound the pavement to find a hospital with quarantine wards and emergency procedures. Of course, it was possible the patient could not be treated on time, so Choi gave up going to Bundang and started calling again.

● Even if you call the ‘hotline,’ the answering machine answers the call

At 9:26 p.m., he made the 23rd call to Hanyang University Guri Hospital. “We cannot answer the phone right now. Please call again.” As he hung up the automatic response system (ARS) phone, Choi remembered a particularly sorry patient last spring. He was making over 30 calls for one 90-year-old grandmother who was not breathing properly.

"Stop trying to find the ER. I want my grandmother to die in the comfort of her home." After wandering around for about an hour, the grandmother's family said. In the end, Choi drove an ambulance to the grandmother's house.

This time, Choi called Ewha Womans University Seoul Hospital. It was the 24th hospital he called. The representative who answered the phone said that it might not be connected to the ER, because too many calls were already being made to the emergency room. In fact, Jeong's phone call did not even reach the emergency room. The hospital's emergency room number given to the ambulance was a make-believe “hotline.” He had to call three times before an ARS or phone representative picked up the phone. Whenever the emergency patient transfer issue was raised, the government came up with a new “hotline” as a countermeasure, but it was nothing but an empty promise.

For the 25th time, Choi called Green Hospital in Jungnang-gu, Seoul, but the hospital did not answer the phone. Now, there were only a few hospitals left in Seoul that he could call. For the 26th time, he called Yeouido St. Mary's Hospital in Yeongdeungpo-gu, Seoul. He had to tell the hospital the same thing over and over again. His patient is a 68-year-old male, who has chest pain, and suffering from shortness of breath… Then the representative said, “Wait a minute,” which followed the playing of standby music, “For Elise.”

Around the time the music played three or four times, the hospital staff said, “I think you can bring the patient.” Finally, the ambulance departed and arrived at Yeouido St. Mary's Hospital at 9:52 p.m. after driving along the Han River. It was after making 31 calls to 26 hospitals. It has been an hour and 15 minutes since Jin-soo's wife called 911. Like Jin-soo, the number of patients who took more than an hour to reach the emergency room after the ambulance dispatched was 196,561 nationwide in 2021 alone. That's one every three minutes.