Dementia patients exploited as justice fails to intervene

Dementia patients exploited as justice fails to intervene

Posted December. 16, 2025 08:28,

Updated December. 16, 2025 08:28

On a street in Nonsan, South Chungcheong Province, in October 2021, as autumn deepened, an elderly man with dementia wandered aimlessly in worn clothing. Identified as Jeong Soon-ho, a pseudonym, 71, he could not recall his own name or age when an investigator from a senior protection agency arrived following a report. He repeated only a single sentence, again and again. “The money. I have to get the money back.”

The state of Soon-ho’s bank account revealed the scale of his loss. Since July 2020, more than 200 million won had flowed out through dozens of transactions. A former junior colleague from his workplace, 69, who had taken charge of managing his finances after the onset of dementia, emerged as the prime suspect. Records showed that large sums had been transferred to accounts held by the colleague’s daughter and other acquaintances.

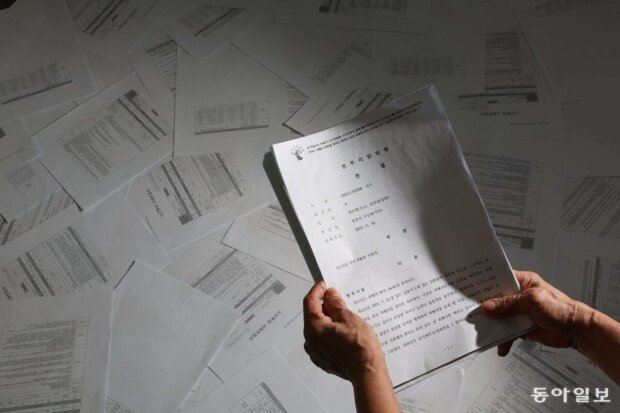

The case, however, never reached the police. The colleague had arranged for Soon-ho to carry out each transfer himself, and the inconsistent testimony of a dementia patient was deemed insufficient to prove embezzlement. The agency attempted to recover the money by acting as legal guardian, but the colleague’s daughter and acquaintances had already declared bankruptcy and gone into hiding. Soon-ho died last month in a nursing facility without recovering most of his savings. His suffering now remains only in a single-page abuse determination report filed by the senior protection agency.

Crimes that target the assets of elderly people with dementia are widespread, yet their true scale remains unknown. No comprehensive fact-finding effort has ever been conducted. How much money is lost, and how systematically it is taken, remains largely unmeasured. Over the past five years, an estimated 67,443 dementia patients are believed to have fallen victim to financial crimes. Yet court verdicts identify only 49 confirmed victims. Even if there were 1,000 victims, fewer than one perpetrator would be held criminally accountable.

To illuminate this hidden reality, the Dong-A Ilbo Hero Content Team analyzed 379 cases of economic abuse involving elderly dementia patients documented over five years by senior protection agencies under the Ministry of Health and Welfare. The aim was to capture the scope of abuse that never appears in official statistics. Of those cases, only 34, or 8.9 percent, were ever recognized by investigative authorities. The rest effectively disappeared. Within those files were the silenced cries of elderly people who lost lifelong savings to children, trusted caregivers or acquaintances, and who remained silent because they were told it was family, or because dementia stripped their words of credibility.

![[단독]“거부도 못해” 요양병원 ‘콧줄 환자’ 8만명](https://dimg.donga.com/c/138/175/90/1/wps/NEWS/IMAGE/2026/03/02/133450041.2.jpg)