Voters doubt candidates’ plans to fix the economy

Voters doubt candidates’ plans to fix the economy

Posted May. 22, 2025 07:42,

Updated May. 22, 2025 07:42

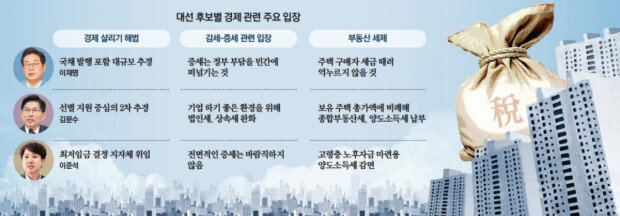

With just 12 days until South Korea’s presidential election, candidates are ramping up their economic pledges. Lee Jae-myung of the Democratic Party is pushing for a supplementary budget financed through government bonds, while Kim Moon-soo of the People Power Party is advocating tax cuts. Though both plans could temporarily lift the economy, critics say they do little to address the deeper issues behind Korea’s declining growth potential.

Lee has pledged to “write off small business debt through a supplementary budget and issue local currency to spur spending.” Following the 13.8 trillion won package passed earlier this month, he is calling for a second round of fiscal stimulus aimed at easing burdens on the self-employed and reviving consumption.

Kim, for his part, said he would lower the top corporate tax rate from 24% to 21% and loosen regulations to encourage investment. He is also open to a second supplementary budget but sees tax relief as the centerpiece of his strategy.

What both proposals share is the significant pressure they would place on government finances. Whether by issuing more bonds or cutting revenue, both paths lead to a larger fiscal gap. National debt is projected to surpass 1,200 trillion won in the first half of the year. Further bond issuance could depress bond prices and raise market interest rates—or at least slow their expected decline. In that case, policies meant to support businesses and the self-employed could have the opposite effect, increasing interest burdens and discouraging investment.

Both candidates have also made AI investment a central part of their platforms. Yet experts note that the scale and timeline of such projects are difficult for the private sector to handle alone. Lee has proposed gradually raising funds through private capital, while Kim calls for a public-private AI fund.

Critics see a contradiction: while both are willing to take on debt for voter-pleasing policies, they prefer to shift the cost of long-term innovation to the private sector. Neither campaign offers detailed support measures for critical industries like semiconductors, electric vehicles, and batteries—sectors vital to Korea’s future competitiveness.

If politicians want to justify borrowing money that future generations will have to repay, they must clearly show how those funds will grow the economy and benefit those generations. That kind of vision is missing from both campaigns. No wonder the public is watching with more concern than hope.