Patients adrift in emergency rooms, going as far as 152 kilometers to find hospital beds

Patients adrift in emergency rooms, going as far as 152 kilometers to find hospital beds

Posted March. 29, 2023 08:21,

Updated March. 29, 2023 08:22

“Is his WBC (white blood cell) count 30,000?”

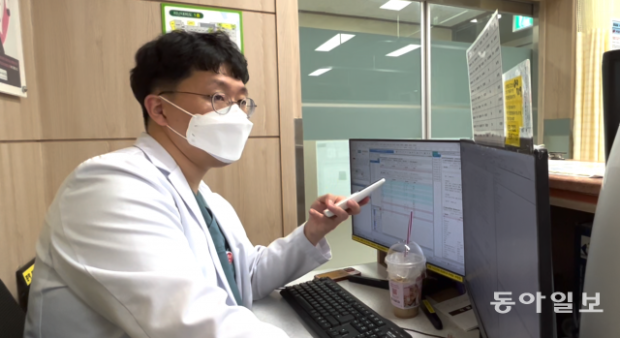

Dr. Kang Gyung-guk, chief of emergency medicine at Yeosu Jeonnam Hospital, looked at the test result in shock. The patient’s WBC count was three times higher than normal, indicating serious health problems with an unknown cause. Dr. Kang hurriedly placed a phone call to transfer the patient to another hospital for hemodialysis treatment.

Even if a patient makes it to the emergency room, he may still have to stay afloat to see a doctor finally. This was the case with Jang Boo-gwi, aged 74, who was moved to the emergency room at Yeosu Jeonnam Hospital in Yeonsu, South Jeolla Province.

● Patients endlessly awaiting doctors in the hustle and bustle of the emergency room

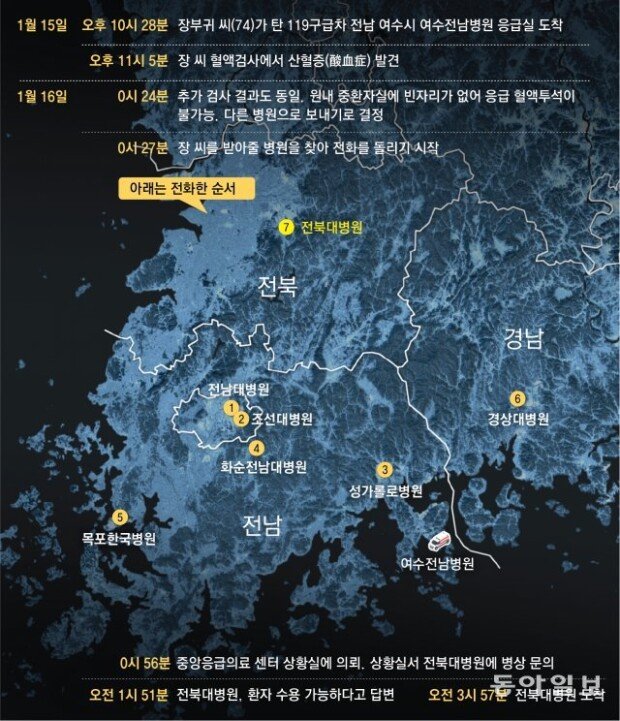

At 10:25 p.m., the phone at Yeosu Jeonnam Hospital’s emergency room was ringing. It was from the 119 rescue center asking if they could transport a patient. “Come,” the ER nurse said.

An ambulance arrived three minutes later, where Jang was lying on the ambulance stretcher. “My husband has diabetes, but his condition was normal. Then suddenly, he became incapacitated,” Jang’s wife explained.

The emergency room was filled to capacity. A man in his 50s showing symptoms of bloody stools seemed to be in a critical condition; a drunken couple in their 20s yelled out loudly; a seven-year-old boy lying beside the couple was getting an IV for high fever. It was a common sight in the nighttime emergency room.

Jang’s test result showed a white blood cell count high enough to stop the heart. “Bring a urinary catheter!” Startled by the test result, Dr. Kang shouted and took off his gown. Dr. Kang hurriedly injected a drug, although he was unsure whether it would have a meaningful effect. The patient would have to be placed on hemodialysis. Yet, the ICU was already full, and there was no patient on the 11 ICU beds whose symptoms were less critical than Jang's.

At 11:30 p.m., Jang went for further tests after taking emergency treatment. Kang returned to his seat, and his forehead frowned with worry. After taking a sip of water, Dr. Kang opened a 1,300-page emergency medicine textbook and searched relevant academic papers on Google.

Dr. Kang needed to check Jang’s medications. Jang’s family took a photo of pharmacy envelopes, but it was difficult to read the details because the letters were too small. Dr. Kang wished to see the patient’s medical records, but medical records from other hospitals were inaccessible. Although the government encourages people to download a smartphone application for personal medical records, Dr. Kang has never seen an elderly patient with the application on his or her smartphone.

“Your husband may need to be transferred to a university hospital,” Dr. Kang told Jang’s wife about the patient’s status. “The condition is critical, so call your children.” Pale with fear, Jang’s wife called her kids.

● The only doctor in the ER is busy looking for hospitals instead of providing treatment

Twenty-four minutes after midnight, the test results showed that Jang was in critical condition. The medicines were not helping. “Let’s transfer the patient to other hospitals. His blood test results are very bad.”

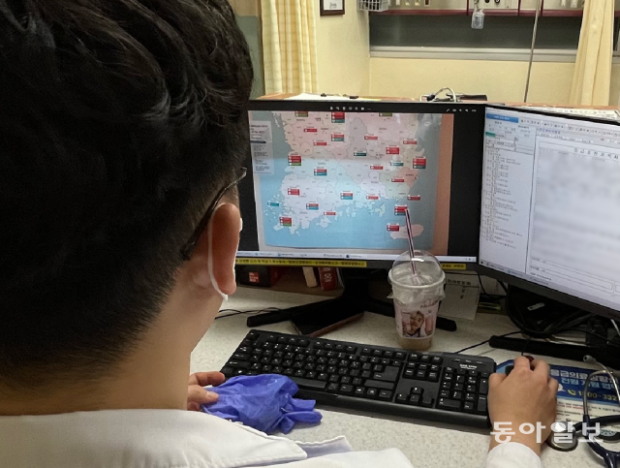

Then came the usual phone calls after phone calls. Dr. Kang started to make phone calls to hospitals with empty beds in the ICU, from the nearest to the farthest away. When a hospital denies the admission, he calls another hospital. Although the central emergency medical center website shows the occupancy of hospital beds, Dr. Kang knows well more than anyone that the number tells nothing. Even if there are empty beds, they are meaningless if there is no doctor to treat patients.

“Hello. We have a 74-year-old male patient who needs emergency hemodialysis.”

Dr. Kang irritably tapped a button to end a call. “Chosun University Hospital said no,” he said, growing more anxious. He made ready the automatic cardiac compression machine and respirator in an emergency. Nearby hospitals that could administer hemodialysis are in Gwangju, one hour drive northward from Yeosu Jeonnam Hospital. However, both Gwangju Jeonnam University Hospital and Chosun University Hospital said beds were unavailable.

Dr. Kang kept making a call only to get turned down. Three large-sized hospitals in Suncheon City, Hwasun County in South Jeolla, and Mokpo City also said they could not take Jang. Dr. Kang even called Gyeongsang University Hospital in Jinju City in South Gyeongsang Province, but the answer was no. “It was the last hospital,” Dr. Kang murmured.

The only hope was that no other severely ill patient was coming in. Dr. Kang was the only ER physician on this day, and thus there was no room for more patients. Except for 38 regional emergency medical centers out of 516 emergency rooms nationwide, only one emergency room doctor oversees the entire emergency room.

● 152 kilometers of travel to find an empty hospital bed

At 12:56 a.m., Dr. Kang placed a phone call to the central emergency medical center’s situation room, an organization that arranges an available hospital bed for critically ill patients who cannot receive treatment at an emergency room. Dr. Kang did not call the situation room immediately because it is overflowing with demands from across the country. Four to six permanent staff in the situation room look for hospital beds by making calls individually. This is practically the same process Dr. Kang took. It is the last resort.

After having a phone conversation with the situation room, Dr. Kang brought a map with major emergency rooms across the country and direct lines on the monitor. “I hope we do not have to go too far.”

At 1:51 a.m., Jeonbuk University Hospital in Jeonju City, North Jeolla Province finally said it could admit a patient. It was the hospital arranged by the situation room. Although the hospital was a two-hour drive away, there was no other choice. Dr. Kang told Jang’s wife right away that Jang will be transferred to Jeonbuk University Hospital by crossing the provincial border. “Jeonju?” Jang’s wife asked back. “Yes, the nearest hospital is in Jeonju,” Dr. Kang replied.

A nurse hailed a private ambulance to take Jang to Jeonbuk University Hospital. The ambulance drove 152 kilometers and arrived at Jeonbuk University Hospital emergency room at 3:57 a.m., three hours and 30 minutes after Dr. Kang started to make phone calls. In 2021 alone, a total of 483,781 patients were admitted to the emergency room via other hospitals. Jang was one in every 10 patients in the emergency room patients.

![[사설]참 구차한 김병기 전 원내대표](https://dimg.donga.com/c/138/175/90/1/wps/NEWS/IMAGE/2026/01/13/133151454.1.jpg)