Science and society intersect through diesel and biodiesel engines

Science and society intersect through diesel and biodiesel engines

Posted December. 06, 2025 07:16,

Updated December. 06, 2025 07:16

When Christmas carols start filling the air in December, diesel engines may not seem like an obvious association, yet they often come to mind. The reindeer that pulls Santa Claus’s sleigh is named Rudolph, and the inventor of the diesel engine also happened to be Rudolf Diesel. Among humans named Rudolf rather than reindeer, Diesel is undoubtedly the most referenced figure.

In the late 19th century, after gasoline-powered engines were invented, Rudolf Diesel set out to create an engine that could run not only on gasoline, which was in short supply at the time, but also on a wide range of oils including sesame oil and perilla oil. As a result, diesel engines are capable of operating on many different fuels, from light oil to heavy oil. With appropriate engineering, even regular cooking oil can be used to power a diesel engine.

A popular 21st century innovation that takes advantage of this feature is biodiesel. Biodiesel refers to fuel made by processing vegetable oil so that it can be used in a standard diesel engine. The most common example is biodiesel made from canola oil, which is an edible oil, and discarded cooking oil can also be collected and converted into biodiesel. Because biodiesel is produced through farming rather than extracted from underground like petroleum, it can be generated continuously without the risk of depletion. It also releases less carbon dioxide, since its source crops absorb carbon through photosynthesis. For this reason, biodiesel is widely regarded as an environmentally friendly fuel.

Not surprisingly, Germany and other European countries that have long led the way in environmental technology tend to favor biodiesel. When governments introduce programs that encourage the widespread use of biodiesel for environmental protection, they can also support European companies that produce it. South Korea, by contrast, has no crude oil reserves of its own but has built a highly developed refining industry that exports gasoline, kerosene and other petroleum-based products around the world. As European policies increasingly promote biodiesel over petroleum, European consumers are turning to Europe-made biodiesel instead of petroleum products exported from South Korea.

Environmental agencies in advanced economies often work closely with domestic industries and use environmental issues as a means to drive industrial growth. The persistent belief that environmental protection requires suppressing industry or opposing corporations remains widespread, yet the reality is far more complex. China has recently attempted to leverage its agricultural output and advanced chemical technologies to sell biodiesel in Europe, and Europe now appears to be moving again to revise its policies in response to block the growing influx of Chinese biodiesel. South Korea, I believe, needs similar efforts by treating industry not as an adversary but as a partner and by seeking ways to achieve both environmental protection and economic growth.

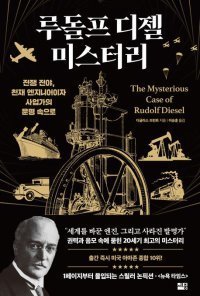

“Rudolf Diesel: The Mystery” explores the life of Rudolf Diesel and the unanswered questions surrounding his final days through extensive documentation and meticulous research. To illustrate how the diesel engine emerged and rose to global prominence, the book also details the broader social landscape of the period, including industrial transformation, economic upheaval, politics, and the march toward war. It makes an engaging companion for a long winter evening, offering both leisure and a collection of compelling human stories. It is also a valuable read for understanding how a single scientific breakthrough can reshape society, much like the current debates surrounding biodiesel.

![1평 사무실서 ‘월천’… 내 이름이 간판이면 은퇴는 없다[은퇴 레시피]](https://dimg.donga.com/c/138/175/90/1/wps/NEWS/IMAGE/2026/03/06/133479845.5.jpg)

![한국 성인 4명 중 1명만 한다…오래 살려면 ‘이 운동’부터[노화설계]](https://dimg.donga.com/c/138/175/90/1/wps/NEWS/IMAGE/2026/03/06/133478051.3.jpg)

![미국은 미사일이 부족하다? 현대전 바꾼 ‘가성비의 역습’[딥다이브]](https://dimg.donga.com/c/138/175/90/1/wps/NEWS/IMAGE/2026/03/07/133477062.1.png)