Lee proposes incentives to keep production in Korea

Lee proposes incentives to keep production in Korea

Posted April. 25, 2025 07:21,

Updated April. 25, 2025 07:21

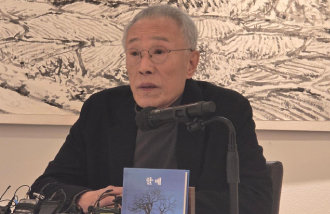

Former Democratic Party leader Lee Jae-myung is reportedly preparing a sweeping overhaul of South Korea’s tax code as a central pledge in his presidential campaign. At the heart of the plan is a proposal to provide tax credits to companies that keep their production facilities in Korea—a bid to stem the outflow of manufacturing operations to overseas markets. While the proposal signals a clear intent to boost domestic investment and create jobs, critics argue that corporate tax incentives alone may not be enough to counter the powerful forces driving Korean companies abroad.

Lee’s pledge, dubbed the “Korean version of the IRA,” comes in response to a global trade realignment triggered by former U.S. President Donald Trump’s steep tariff policies. It also draws parallels to the Inflation Reduction Act passed under President Joe Biden, which offers generous subsidies and tax breaks to electric vehicle and battery makers investing in the United States. In response, many Korean exporters are now considering expanding operations in the U.S. to mitigate tariff impacts. At home, South Korea is grappling with a weakening manufacturing base and mounting job losses. Offering incentives to companies that retain or expand domestic production is therefore seen as a timely, well-intentioned step.

Still, whether modest tax breaks can offset broader structural factors—like lower labor and energy costs in Southeast Asia or tariff exemptions in the U.S.—remains in question. For many firms, decisions to relocate production are driven by existential calculations. Similar “reshoring” policies introduced by past administrations have failed to produce meaningful results.

Rather than relying solely on tax incentives to counter Washington’s tariff pressure, many argue that Korea should focus on removing the root causes that push firms to leave in the first place. Chief among these is the country’s inheritance tax—the highest among OECD nations.

South Korea’s top inheritance tax rate stands at 50%. With a 20% surtax on majority shareholdings, the effective burden can reach as high as 60%. This has led many family-run firms to sell stakes to private equity funds to cover the cost, often resulting in reduced domestic investment and job cuts. A sound economic strategy requires an honest assessment of such structural hurdles. If the next president wants businesses to stay, grow and hire at home, they must go beyond production incentives and pursue bold reforms—starting with a cut to inheritance taxes.

![[김순덕 칼럼]지리멸렬 국민의힘, 입법독재 일등공신이다](https://dimg.donga.com/c/138/175/90/1/wps/NEWS/IMAGE/2025/12/09/132934565.1.jpg)

![[속보]‘통일교 의혹’ 전재수 장관 사의…“직 내려놓고 허위 밝힐 것”](https://dimg.donga.com/c/138/175/90/1/wps/NEWS/IMAGE/2025/12/11/132943538.1.jpg)