Appetite Has Written the History of Humans

Appetite Has Written the History of Humans

Posted February. 25, 2005 23:09,

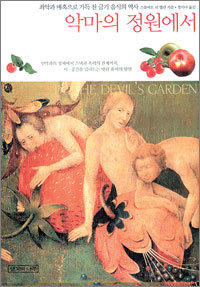

Imagine a garden with all kinds of fruits and vegetables of different colors. Imagine that in this garden are fish swimming in creeks, birds flying between tree branches, and plump animals attracting your attention. Why would this garden be called the Devils Garden? This garden allows humans simply instinct and so makes them indistinguishable from other animals. Also, it is filled with various kinds of magic, incantation, and taboos. This is the garden of appetite. The author of the 2002 book, In the Devils Garden is an American journalist who has worked as a chef, theater director, and a farm worker, and has explored the history of instincts and taboos that humans peppered upon food in different civilizations at different times. Why dont you join in the exciting journey of food exploration?

Parisians have been accustomed to the sour taste of bread for a long time. When a bread, pain mollet, with the soft texture of a babys bottom appeared on the meal table, a series of arguments occurred. When it was revealed that some bakers were using Belgium yeast for pain mollet, the bread was stigmatized as the bread that instills an unpatriotic character. The Council of Paris Medicine ultimately banned the distribution of the bread. Vehement supporters of pain mollet forced the government to retract the ban. The answer is soft bread.

In the movie Amadeus audiences see a snack shaped like a breast and topped with a cherry. This pastry is called the minni di virgini, literally the teats of virgins bosom, and was made to applaud the female saint Agatha who died after being tortured. Heretics cut off Saint Agathas breasts because she refused to deny her faith in Christ. In medieval paintings, Saint Agatha is often depicted holding up a dish with her breasts on it. She is often seen as the patron saint of breast cancer patients. The answer is breasts.

In the mid-1800s the British East India Company armed the Indian soldiers with Enfield rifles. These rifles were more exact in targeting and faster to chare than other guns. To maximize these abilities, oils and fats needed to be applied to the cartridge. The English used fats from pigs and cows, which was offensive to both the Muslims and the Hindus. Those soldiers noted, if we touch this cartridge, we would be the untouchable. The soldiers eventually rebelled against their colonizers. The answer is oils.

In the Middle Eastern region there is a plant called Lecanora esculenta that becomes swept away by the strong wind of the deserts. When it is swept away, it often lands far away, and when it is released from the air it appears to simply fall from the sky. Local people use the plant when making bread and jellies. The plant is mentioned in the Bible: Being sick of the food, Manna, the Jewish returning to Israel expressed their complaints. And, Jehovah sent quails but it turned out a big calamity. It has been suggested that the quails ate poisonous henbane or moss which caused stomachaches for the Jewish persons who then ate the birds. The answer is moss.

Traditionally, Italians have used basil in making pasta. Basil is covered with a cotton fluff on its top, and it is believed that one must curse when looking at the head of the plants. Romans believed that If you smell the basil the scorpion appearing in legend, basilisk, would grow in your head. However, if you use your tongue for a curse the rigor of the scorpion would debilitate. This legend came from basils uniquely strong smell, which was believed to disturb peoples minds. The answer is swearing.

Globalization makes exotic foods more accessible and therefore less mysterious. Food has lost its role as a soul soother; instead, it is now considered a fuel to ensure physical well-being. We should think the story we once had about each fruit, plant, root, and animal in the forest, before we met them on our meal tables. After you read In the Devils Garden your meal table will look different.

Yoon-Jong Yoo gustav@donga.com