Need for increased funds for emergency surgery

Need for increased funds for emergency surgery

Posted April. 04, 2023 08:09,

Updated April. 04, 2023 08:09

"Drifting," which is the word to describe emergency patients drifting helplessly without treatment, has become an everyday occurrence. If the cause of this problem is left untapped, people will continue to lose their life in an ambulance or in the emergency room.

The solution to ending this "drifting" is simple. We need more surgeons. We need to fix the system that connects them to patients. It's a solution that the government and the National Assembly are already aware. They are just turning a blind eye to their obligation to implement them.

The 4th Basic Plan for Emergency Medical Care, released by the Ministry of Health and Welfare on March 21, was no different from what it has been saying all along. There were no bold action plans. The Dong-A Ilbo Hero Content Team tried to rewrite some parts of the basic plan. After in-depth interviews with 26 patients who were left adrift and more than 100 medical staff and paramedics in the field from October last year to March this year, we came to the following conclusions.

● Government measures strayed from reality

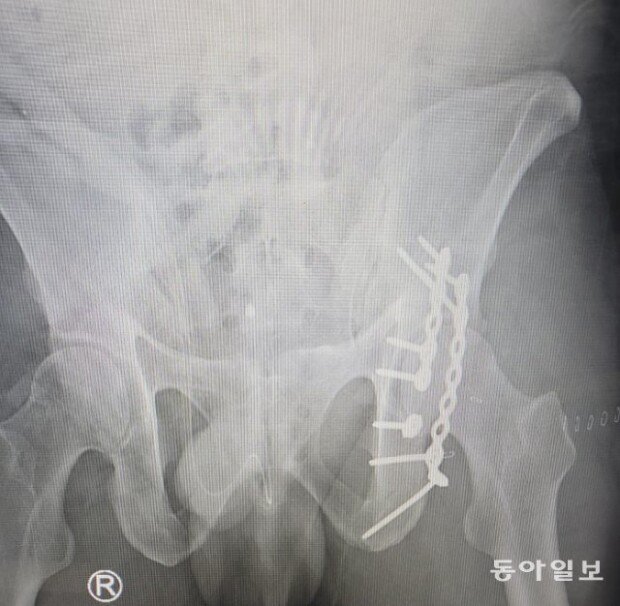

Bae Byeong-in, aged 40, a father of two children in elementary school, shattered his pelvic bone in a car accident in Andong, North Gyeongsang Province, on Dec. 17 last year. He was rushed to Andong Hospital in 28 minutes, but there were no doctors available for surgery at seven nearby hospitals, including Andong Hospital. Three other hospitals said they had doctors, but they were already operating on another patient. Bae was transferred to a hospital about 220 kilometers away after five hours and 35 minutes after the accident.

The shortage of surgeons was one of the most fundamental problems of drifting. Emergency patients need to move uninterrupted from an ambulance to an emergency room to an operating room. However, if there are no doctors in the operating room, each step is clogged, and patients are left on the street.

The Health Ministry has proposed a "rotating on-call system" to solve this problem. For example, a doctor at Hospital A who can perform emergency surgery for brain hemorrhage would stay on duty on Monday and another doctor at Hospital B on Tuesday.

However, this is just a "tabletop administration" that ignores the reality that there is a shortage of surgeons. Some hospitals with a regional trauma center can't even find vascular surgeons to prevent limb amputations.

The same goes for the measure to increase the number of pediatric emergency medical centers from eight to 12 nationwide to provide 24-hour care for critically ill children in need of surgery. Some of the eight designated centers are already facing the risk of closure because they can't find surgeons.

Some point out that fundamental measures are needed, such as significantly increasing the compensation for emergency surgeries and reflecting the acceptance rate of severe emergency patients in the evaluation of high-level general hospitals. This would require redirecting health insurance funds from unnecessary tests and minor treatments to emergency surgeries. The current system of “relative value units," which is structured to set low prices for emergency surgery, should also be reformed. The government and lawmakers have been putting off this reform for fear of backlash from reducing the number of policy beneficiaries.

● Real-time communication among 119-ER-Operation rooms are needed

In order to minimize the time spent searching for hospitals capable of treating emergency patients, an efficient system is crucial for identifying suitable facilities.

The tragic death of a 17-year-old girl, who fell from an apartment building in Daegu last month, highlighted the absence of such a system. During the emergent situation, the ambulance crews had to drive around multiple emergency centers, unaware of the hospitals' treatment capacities, while the situation room relied on inaccurate information to contact hospitals.

The Ministry of Health and Welfare recently proposed a plan to create a system that “transmits patient information, entered by 119 ambulance crews on their tablets, to designated hospitals." Considering the so-called ‘ambulance merry-go-round’ phenomenon experienced by many emergency patients, sharing patient information from the initial inquiry stage is essential for timely transfers.

However, the proposal to establish additional situation rooms to assist with inter-hospital transfers remains uncertain due to recent budget cuts for staffing at the National Emergency Medical Center's situation room. An official from the Ministry of Health and Welfare disclosed, "There is no budget for setting up regional situation rooms this year, and it is unlikely to be secured next year either."

● ER needs categorization by severity levels

Mild cases utilizing 119 ambulances as if they were taxis contribute to response delays. On December 19th last year, a cardiac arrest patient was reported in Jayang-dong, Gwangjin-gu, Seoul. With the survival rate for cardiac arrest patients plummeting by 7-25% for each minute that CPR is delayed, prompt response is critical. Unfortunately, the Jamsil 119 ambulance crew from Songpa Fire Station, located 10 minutes away by car was dispatched. It was due to closer crews was attending to non-urgent cases, such as callers complaining of excessive phlegm or throbbing feet.

Overcrowded and chaotic emergency rooms in large-scale general hospitals further exacerbate the consumption of crucial response time. Although their emergency rooms bustle with patients every evening, two-thirds of these individuals have mild conditions that could be addressed at smaller facilities. Even during the visit of the Dong-A Ilbo reporter to an emergency room to cover this story, one patient was demanding treatment because his ‘palm had turned white after holding a bag for an extended period.'

It is time to consider implementing measures that impose significant costs on those who repeatedly call ambulances or visit large hospital emergency rooms without any symptoms. At present, the only disadvantage for mild cases using large hospital emergency rooms is an additional emergency medical management fee of approximately 40,000 won. In Japan, ambulance crews can refuse to transport mild cases, and non-emergency patients using large hospital emergency rooms are charged hundreds of thousands of won in medical fees.

![‘삐∼’ ‘윙∼’ 귓속 소리… 귀 질환 아닌 뇌가 보내는 잡음일 가능성[이진형의 뇌, 우리 속의 우주]](https://dimg.donga.com/c/138/175/90/1/wps/NEWS/IMAGE/2026/03/10/133505001.1.jpg)