Fate of poet

Fate of poet

Posted February. 11, 2022 07:36,

Updated February. 11, 2022 07:36

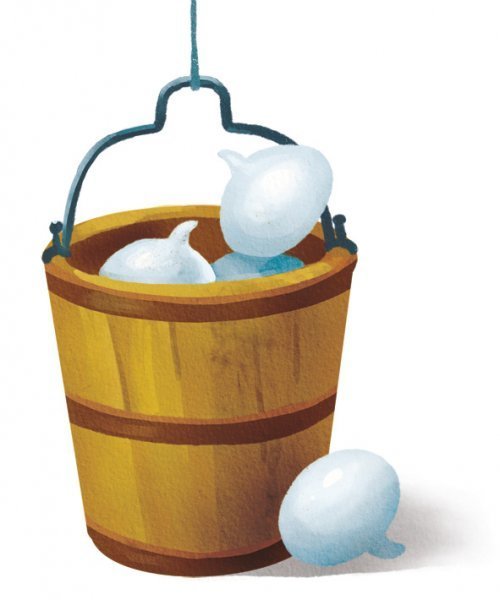

If poetic inspirations are likened to well water, a set of a brush and an inkstone may be a pulley. As you keep reciting your poetic ego’s voice, such recitals work like a pully rope to raise water from the well. It is a duty of poets to recite poems with their lips while letting their hands work to raise poetic phrases of freshness and cleanness from the bottom of their heart. If they stop drawing water from a well, water deep inside goes bad or dries up. What is the use of drawing well water on and on? It is not to show an outstanding level of taste or poetic talent.

It all comes down to a chronically strong and deep desire to try to contemplate and choose the perfect poetic language. That may be why a poet said, “It took as many as three years to complete just a couple of lines. Reciting them only gives me tears.” This only makes us take it seriously that every letter is full of anguish and agony, which may never be said jokingly. Afraid to come across fussy, he even adds the word “jokingly” to the title of his poem. The poet’s weary fate of never stopping drawing water from a well must have resonated with his friend.

A group of poets called Goeumsipa are characterized by their continued pursuit of finding the perfect phrases and mending them repetitively despite agony and pains. We are not sure from which such a writing style came, painful feelings in real life or artistic perfectionism, but this highlights a quality freshly different from what we can find in Li Bai, who once showed the nonchalance of his gallant ego by saying that he wrote a hundred pieces in return for a drum of liquor.

“Licking his wounds/ for his lifetime/ not just once/ but too many times/ not just too many times/ but throughout a whole lifetime/ taking care of his own wounds/a poet dying slowly.” (“Poet” by Na Tae-joo) Every step taken by poets of both the past and today always leads them in the same direction of fate.