In Search Of

Todays equivalent to Gosanja (the nickname of Koreas historic cartographer) would undoubtedly be Shin Jeong-il. For 25 years he traversed 30,000 li (approximately 12,000 km) of every corner of the nation. Streams and mountains, old roads and villages, all were meticulously canvassed by Shin. He would walk and read, or walk and write at the same time. His life was his path, and his path was his life.

Having produced groundbreaking publications with this effort, this time around he has retraced Gosanjas steps by zoning into his beloved land, Daedongyeo.

The focus of Visiting the traces of Old Villages with the Daedongyeojido is on 90 villages that were eradicated with the revision of Joseons eight provincial districts during the Japanese occupation in 1914.

The scenery perceived through his eyes is replete with loneliness and anger, love and empathy. His microscope functions in three colors. In book 1 he deals with past prosperity. By focusing on Eunjin (Ganggyeongpo-gu), a large commercial district that has since been relegated to a small salted fish market, or Gobu, formerly the largest village in Jeolla province that disappeared during the Donghak Farmers Movement, he expresses his anger against the travails of the countrys history.

Though walking a difficult journey, he does not fail to lose sight of the scenery. In book two he approaches the story behind the villages that have disappeared due to its beauty in more depth. Such examples include Danyang of Chungcheong Province and Yongdam of Jeolla Province, which were erased from the map by the construction of dams or the development of the land. This is precisely why this book is referred to as a historical book that mimics a travel book. The authors exemplary photo skills heighten this sense of perception.

Given that great figures are produced from the energy of the mountains and the waters, it seems only natural that the authors attention is directed to people. Thus in book three he deals with stories centering people such as Kim Hong-do of Yeonpung, Chungcheong Province, Moon Ik-jeom of Sancheong, Gyeongsang Province, and Cho Gwang-jo of Neungju, Jeolla Province. Rather than limiting the stories to the people, he also introduces stories linked to the regions. At this point the readers can discern that the author has amassed our traditional legends in geographical terms.

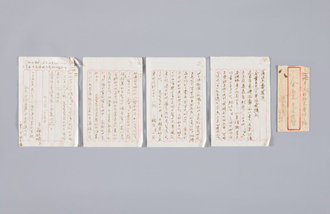

Before the project Shin Jeong-il published five books on The New Taekriji. The book is a modern rendition written by tracing the steps of Lee Jung-hwans liberal arts publication Taekriji. Introduced this time around, Visiting the traces of Old Villages with the Daedongyeojido is significant in that it focuses on the Daedongyeojido that was produced 150 years ago. The lens that the author applies is all the more clear as he perceives the realities of the land beyond a mere dimensions of a faded map.

The past may seem nostalgic due to frustrations of the present or from a vague yearning. Daedongyeojido is no longer present as a map, but rather as a historical record. Land also changes with age. This book serves as a mirror of the past that in turn reflects our present era, which is why its emotions resonate with the turning of each page.