Life like Mulch, Life Energy Like Weeds

Life like Mulch, Life Energy Like Weeds

Posted May. 28, 2004 22:46,

My Half Brothers

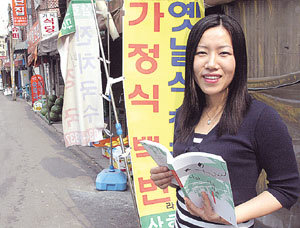

Written by Lee Myeong-rang

300 pages, 9,000 won, Practical Literature Co.

Reading the new book, My Half Brothers, by writer Lee Myeon-rang, 31, makes me think of a seventeen year olds black eyes without a white speck: so black just like a drop of ink. So black and therefore so clear, that is where life starts for Lee Young-won, a wandering seventeen-year-old girl without a home.

The place that she is temporarily staying in, held by Lets-cooperate Uncle, after floating around in the world like a dried leaf on the surface of the water is Seoul Store, a fruit store in Yengdeungpo market in Seoul. It is a small corner store in the market where the author was raised in, sold the fruits in, wrote, and is currently raising her kids.

Lees novel two years ago, Sam-Oh Restaurant, portrayed sagas of tough tradesmen living in the deals and liveliness of the market. This time, the weak mulch, fully exposed to the contempt and violence rampant in the marketplace, are depicted and come to life with Lees pen.

Chun-mi is a frequent visitor to the hospital because of muscle paralysis. Blackie is an illegal migrant worker from India. Moron is a café waitress, a Chinese-born Korean, who is engrossed in making money with prostituting to get a residence certificate while enduring the beating of her pimp. Dwarf Big Eye is only as tall as a six year old. And there is me, Lee Young-won who shares the hurt and her soul with them.

Moron, a waitress at the Rose Café learns the Korean alphabet through reading letters on a fruit box. When she tries to make some money, the pimp comes along and just takes it all away to her last one-dollar bill. Young-won gets her a Korean dictionary and opens a bank account for her.

When Chun-mi could not click the TV remote any more because of her paralysis, Young-won became her fingers.

When Big Eye harasses others with his Jindo dog as part of his distorted sense of inferiority, Young-won makes him surrender by flashing her bare breasts in front of his eyes.

The authors writing keeps running with the lives of the mulch floating over water. It is as flowing as a stream, as quick-witted as the rapids, and as cheerful as waterfalls. The market peoples guileful yet cheerful wit and pleasant tricks shine like a ruby apple in an apple box and a cutlass fish on the board of a fish shop.

The ultimate objects of the authors intention of peeling off the shell and giving freedom in the novel are two people. They are Deok-jin, a wannabe writer who opens other peoples refrigerators to cool down the heat inside his body, and me, Young-won.

Their reality is symbolized by a magpie beating its wings in the basement where Young-won lives in.

The moment that Blackie finally lets the bird go out into the sky is strappingly seized by Young-won, who always carries her camera around her neck.

There is light smearing into the basement. To my eyes, the light was coming only onto the magpie right in front of the stairway. The black eyes of the magpie are like an amethyst absorbing the light. The magpie starts to beat its wings toward the light, which is spread like a road through the darkness.

This heart-pounding scene is matched with her fathers advice that still strikes her ear so vividly. Young-won was a daughter of a shaman.

When her tough mother tried to have Young-shin contact a spirit, the weak father came and ruined the ritual, and Young-won could make a run away from her forced fate.

The father refused to let his daughter to live a possessed life and gave Young-won these last words with his last breath and with the best of his left energy:

Forever, Far away, Run away.

Ki-Tae Kwon kkt@donga.com

![장마당서 옷 팔던 北처녀, 인사동 개인전 열기까지[주성하의 북에서 온 이웃]](https://dimg.donga.com/c/138/175/90/1/wps/NEWS/IMAGE/2025/12/05/132901507.1.jpg)