The Greek Crisis and Welfare Populism

The Greek Crisis and Welfare Populism

Posted November. 08, 2010 11:10,

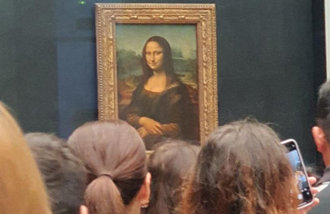

Considered the birthplace of Western civilization and democracy, Greece is a nation that takes great pride in its ancient roots. The country, however, is in chaos. The streets near the capitals Syntagma Square are occupied by union activists outraged by the harsh austerity measures of Athens. Last month, Greece`s most famous ancient site, the Acropolis, was shut down for three days due to demonstrations by unionized public servants.

The Greeks work relatively fewer hours and enjoy more welfare, but their government is having difficulty in tightening the peoples belts. Tourism accounts for 19 percent of GDP, but the industry appears to have reached its limit in its reliance on cultural heritage. This explains the dire Greek situation even after Athens received a loan worth 110 billion euros (154 billion U.S. dollars) from the European Union and the International Monetary Fund. The pride of the Greek people has been damaged but they seem not as determined as Koreans, who buckled down to overcome the 1997 Asian currency crisis after Korea was bailed out by the International Monetary Fund.

The Greek economy had grown until around the 2004 Athens Summer Olympics but collapsed with the onset of the global financial crisis in 2008. The era of shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis ended with Greeces flagship shipping industry being overtaken by Korean, Chinese and Japanese competitors. This undermined the Greek manufacturing industry. Excessive reliance on imports resulted in a huge trade deficit, raising private and public debt. Government coffers are empty but welfare spending continues to surge. The share of social welfare in the national Greek budget increased from 25.7 percent in 2008 to 36.3 percent this year.

In 2008, Athens merged 155 state-run pension funds into 13 but soon ran out of provisions, forcing the use of state coffers and loans from neighboring countries. This resulted in a fiscal crisis that spread throughout Europe. In Greece, men receive pension from age 58 and women from age 55. So the Greek people are accustomed to an extremely generous welfare system.

Twenty percent of the economically productive population in Greece works in the public sector. If a civil servants salary is set at 100 percent, the wage of a public sector worker is 110 percent and that of private workers 70 to 80 percent. Staff at state-owned companies can receive pension even if they retire earlier than the official retirement age due to financial reasons, regardless of their length of service. With the main strikers in Greece being central bank employees and state-owned TV reporters, the country cannot properly implement reform.

The Greek crisis shows the level of difficulty in removing excessive welfare once people are used to it. This has important implications for Korea, a country in which damage from welfare populism is spreading.