Trading of secondhand goods gains popularity

Trading of secondhand goods gains popularity

Posted September. 07, 2019 07:42,

Updated September. 07, 2019 07:42

A 30-something man identified by his surname Yoon first came to know “Dangeun (Carrot) Market,” a mobile secondhand goods trade platform, when he moved into his honeymoon home in Suseo-dong in Seoul’s Gangnam district early this year. He thus learned a method to directly trade secondhand products that are still useful with people in his neighborhoods. He found it was very interesting to put on sale at various prices a wide variety of products including a gas oven range (70,000 won or 58 U.S. dollars), a window blinder (10,000 won or 8.4 dollars), a Starbucks diary (6,000 won or 5 dollars), wedding shoes (3,000 won or 2.5 dollars), and a Guinness bear glass (500 won or 4 dollars).

Recently, Yoon sold a brand new Galaxy S10e smartphone (500,000 won or 400 dollars), which he had received as a gift at an event, a Samsung air purifier (230,000 won or 192 dollars), a leg massage machine (80,000 won or 67 dollars), and a trench coat (35,000 won or 29 dollars). He earned a total of 960,000 won (800 dollars) for the past eight months. “It is interesting and exciting to earn cash by disposing of goods that I thought would not be sellable,” Yoon said.

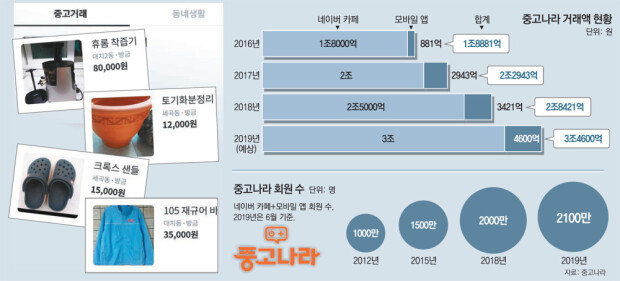

As more people are finding it “exciting to sell stuffs” through mobile platforms for used goods trading, the secondhand goods market is constantly growing. After “Beongae (Lightening) Market” (2010), and “Danggeun Market (2015)”, “Junggonana,” Korea’s No. 1 player in the field, introduced a mobile version (2016) of its service, prompting the Korean secondhand goods market to expand robustly. The value of annual transactions on Junggonara via Naver Café and mobile versions amounted to 2.84 trillion won (2.37 billion dollars) in 2018, and is projected to hit 3.6 trillion won (3 billion dollars) this year. Dangeun Market, the No. 2 player, also saw its annual trade volume jump from 4.6 billion won (3.8 million dollars) in 2016 to 217.8 billion won (182 million dollars) last year, and amount to 339.3 billion won (284 million dollars) through August this year.

“More people are raking in cash by selling goods that are still useful to supplement their disposable income, which has declined amid an economic slump,” said Seo Yong-gu, a business management professor at Sookmyung Women’s University. “As a growing number of consumers are regarding transactions of secondhand goods as a social trend, while platforms for secondhand goods trading have been developed one after another, both supply and demand has grown to strike a right balance.”

Buyers are interested in not only purchasing of goods at bargain prices but also resale values of the products they purchase. Jeong, who has frequently bought secondhand toys for children, hesitated initially when he bought two sets of a 40-book fairytale collection last year. He was worried whether he would be able to resell them because two books of the 80-book series were missing. “I ended up purchasing because I was in a rush and transaction is bothersome, but many mothers seek to buy only ‘A-grade’ products when it comes to book collections to ensure easier resale later on.”

Buyers are also building up know-how and skills to avoid scams. They make direct phone calls with the seller, voice-record conversations, or check the seller’s “history of fake transactions” provided by Junggonara, or use the “Safe Settlement” service when buying goods through a door-to-door delivery system instead of face-to-face transactions. When using the Safe Settlement Service, the buyer sends money to safe transaction service companies including Inisys, and gets delivery of the goods he or she purchases, before pushing the “confirm purchase” button online to allow the payment to be transferred.

hcshin@donga.com

![‘삐∼’ ‘윙∼’ 귓속 소리… 귀 질환 아닌 뇌가 보내는 잡음일 가능성[이진형의 뇌, 우리 속의 우주]](https://dimg.donga.com/c/138/175/90/1/wps/NEWS/IMAGE/2026/03/10/133505001.1.jpg)