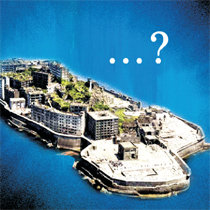

Japan’s Battleship Island trickery

Japan’s Battleship Island trickery

Posted June. 26, 2018 08:01,

Updated June. 26, 2018 08:01

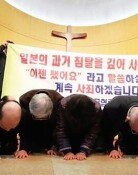

There is a peace museum in Nagasaki. The museum was built in 1995 in memory of Oka Masaharu, a Japanese pastor who devoted his life to finding Korean atomic bomb survivors and promoting the human rights of Koreans living in Japan. In 1974, Oka Masaharu visited Hashima coal mining island (also known as Battleship Island) and found the place riddled with the remains of victims and a list of the dead. The list was fraught with Koreans. This changed his life forever.

In 1988, Han Soo-san, a Korean novelist, stumbled onto a book titled “Atomic Bomb and Koreans” at a book store in Tokyo. The book was penned by Oka Masaharu. The Korean author was greatly shocked by the details of the book, including the Hashima coal mine, forced mobilization and radiation exposures. In 1990, Han began to follow the story himself. He visited the Battleship Island and Nagasaki dozens of times, and met with a countless number of victims. The Korean writer travelled across Japan and even flew to Nevada, the United States where an atomic bomb test was conducted. In 2016, his research bore fruit in the form of a novel titled “Battleship Island.” “I felt ashamed all along, while working on my novel,” Mr. Han recounts.

In 2015, Japan’s industrial facilities including the Battleship Island were designated as UNESCO world heritage. Japan faced criticism that the heritage was spoils of invasion, and it admitted to having mobilized Koreans into forced labor. The country also promised to own up to its past wrongdoings and set up an information center to honor the Korean victims. But the promise was never kept. A new signboard has been installed, but the word “forced mobilization” is nowhere to be seen. According to a follow-up progress report submitted to UNESCO last November, the expression “forced” has been replaced by “supportive,” and the information center is being built not in Nagasaki, but in Tokyo, in the form of a think tank.

UNESCO will adopt a written decision to evaluate Japan’s progress report at the 42nd session of the UNESCO World Heritage Committee, which will be held in Bahrain until July 4. “The fact that the Koreans were forced into labor will be specified in the written decision in the form of footnotes, and we will demand that Japan should implement follow-up measures,” explained an official from South Korea’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs on Monday. The official’s explanation sounds more like a poor excuse, however. Three years have passed, but Japan has not erected a single signboard yet. While the country speaks of a plan to submit an additional report by late 2019, Japan will likely remain tricky to hold accountable.

Kwang-Pyo Lee kplee@donga.com