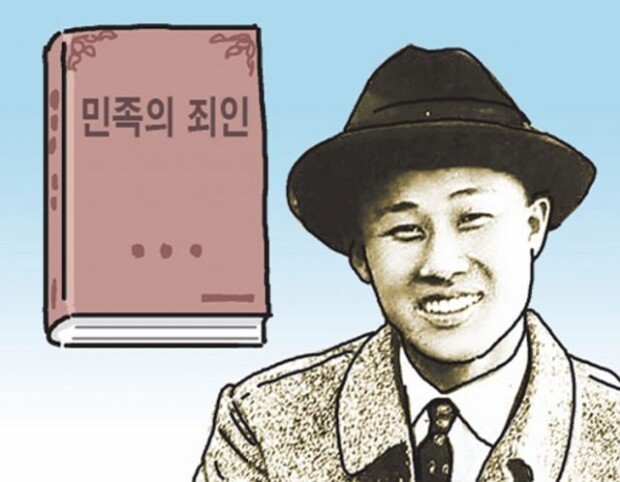

Novelist Chae Man-sik inflicting pain on himself

Novelist Chae Man-sik inflicting pain on himself

Posted November. 17, 2021 07:20,

Updated November. 17, 2021 07:20

“Transgressor of the Nation” written by Chae Man-sik, a novelist famous for his work, “The Muddy Current,” is a novel of confession. It was written in the last years of his short life at 44, six years before his death. It is why the well-crafted novel reads more truthfully.

In the latter years of the Japanese colonial era in 1943, the Japanese Government General of Korea gathered about 200 Korean experts in various fields to have them give lectures condemning the U.S. and the U.K., and praising a war. The narrator of the novel, who is a novelist, was one of them. He had no choice but to follow the order because he knew doing so would guarantee his safety. Even though he did not want to do it, it was his own choice. As Ham Seok-heon, who promoted non-violence movement known as “seed idea (ssi-al sasang),” put it, liberation came like thief, and whatever the reason was, cooperation with the Japanese imperialists constantly tormented the narrator. “The mud of cooperation with Japan that left on my skin was like rubber boots forever stuck on my legs.”

What is ironical is the narrator’s attitude to his nephew. His 20-year-old nephew, who is in his last year of middle school, came to stay in his uncle’s house to study. The students at his school were on a joint leave of absence, protesting that they would not take classes from a pro-Japanese teacher. The teacher failed students, who did not change their family name, followed students and beat them if they spoke Korean. Even after Korea’s liberation, he still disciplined students in Japanese. The nephew came to his uncle’s house with the excuse of preparing for entrance exam and graduation, even though he knew the students’ group action was the right thing to do. The narrator scolded his nephew, saying, “A class president like you should step forward and take the initiative, not take a step back. What you did, therefore, is an act of treason. You might as well die if you intend to act like that.”

But he acted like his nephew, too. Therefore, scolding his nephew was both an education for him, whom he cherished like his own son, and repentance and reprimand for the narrator himself. He tortured himself, calling himself a transgressor of the nation. Ironically, that self-torture was salvation for him. There is no writer in the history of Korean literature who repented the past so bitterly and deeply.

Headline News

- N. Korea launches cyberattacks on S. Korea's defense companies

- Major university hospital professors consider a day off each week

- Italy suffers from fiscal deficits from ‘Super Bonus’ scheme

- Inter Milan secures 20th Serie A title, surpassing AC Milan

- Ruling and opposition prioritize spending amid tax revenue shortfalls